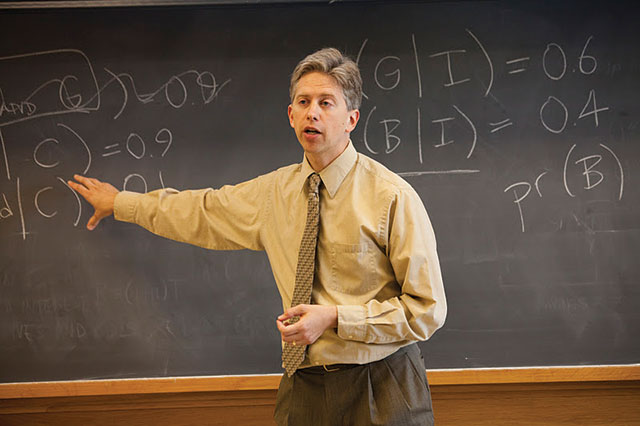

“The public view of Congress is very limited to a few hot-button issues—highly partisan, highly contested ones,” says Craig Volden, professor of public policy and politics at the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. “But hundreds of bills become law, most of them dealing with substantive issues, not just the naming of post offices. This says that Congress is still working. If we only focus on controversies, we are going to miss the rest of it.”

By concentrating on final outcomes and traditional party dynamics, it’s easy even for policy professionals to miss the role individual lawmakers play in shaping policy outcomes. “I was studying members of Congress, but never actually calling them leaders,” Volden adds. “As political scientists, we’ve been thinking of them as the equivalent of voters on the floor of the House of Representatives.” Yet missing from that picture are the leadership skills—expertise, tenacity, persuasion, coalition-building—that make strong leaders elsewhere. Considering these kinds of abilities, Volden wondered, “Is there a way to measure how effectively individual members of Congress propose, promote and pass laws?”

Working in concert with Professor Alan Wiseman of Vanderbilt University, Volden pursued a major research initiative to answer that question. Over a course of two years, Volden and Wiseman developed software algorithms to track and analyze every bill introduced in Congress since 1973, roughly 150,000 and counting. In addition to tallying final outcomes, the system tracks how many bills each member introduced and how far they progressed in the lawmaking process, as well as scoring each bill for its policy impact. Far-reaching bills score higher than commemorative ones. The result is a Legislative Effectiveness Score (LES) for each member of Congress who has served during the past 40 years.