For many would-be leaders and policy experts, goodwill and an earnest desire to help are never in short supply. But when it comes to humanitarian crises, “good intentions aren’t enough,” Batten professor Kirsten Gelsdorf says. “The question is, how do you analyze options and make difficult decisions when you’re trying to work with communities in critical situations, where people’s lives are often at stake?”

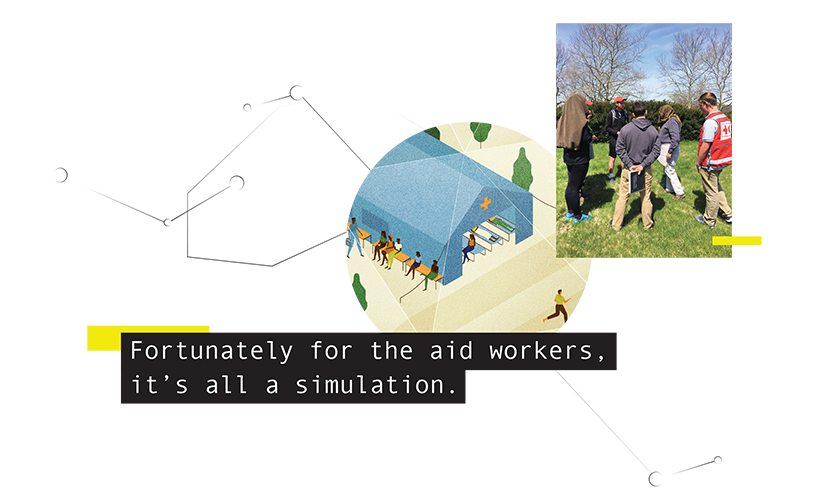

To educate Batten majors on how to excel in such situations, Gelsdorf orchestrates a field training and simulation event in Virginia’s rural Clarke County. The three-day affair is the culmination of a capstone course offered for a small number of fourth-year students. It’s staged by Global Emergency Group, a consulting organization that provides similar trainings for humanitarian and security professionals in the United States and around the world.

“The experience itself is really incredible,” says Batten alum Jonathan Meyer, who participated in the simulation this past spring. “It definitely exposes you to things that you’ve never experienced before, in situations you probably never even imagined.”

Such experience-based opportunities characterize the Batten School’s commitment to preparing consequential leaders, says Dean Allan Stam.

“We’re not just preparing lower- to mid-level bureaucrats,” Stam says. “That was not Frank Batten’s vision. He wanted to recruit, train and place leaders who will make a real difference.” That vision informs a broad range of international research projects spearheaded by Batten faculty. It also helps forge strategic relationships, building networks that enhance the School’s presence around the world.